Reflections

June, 2025

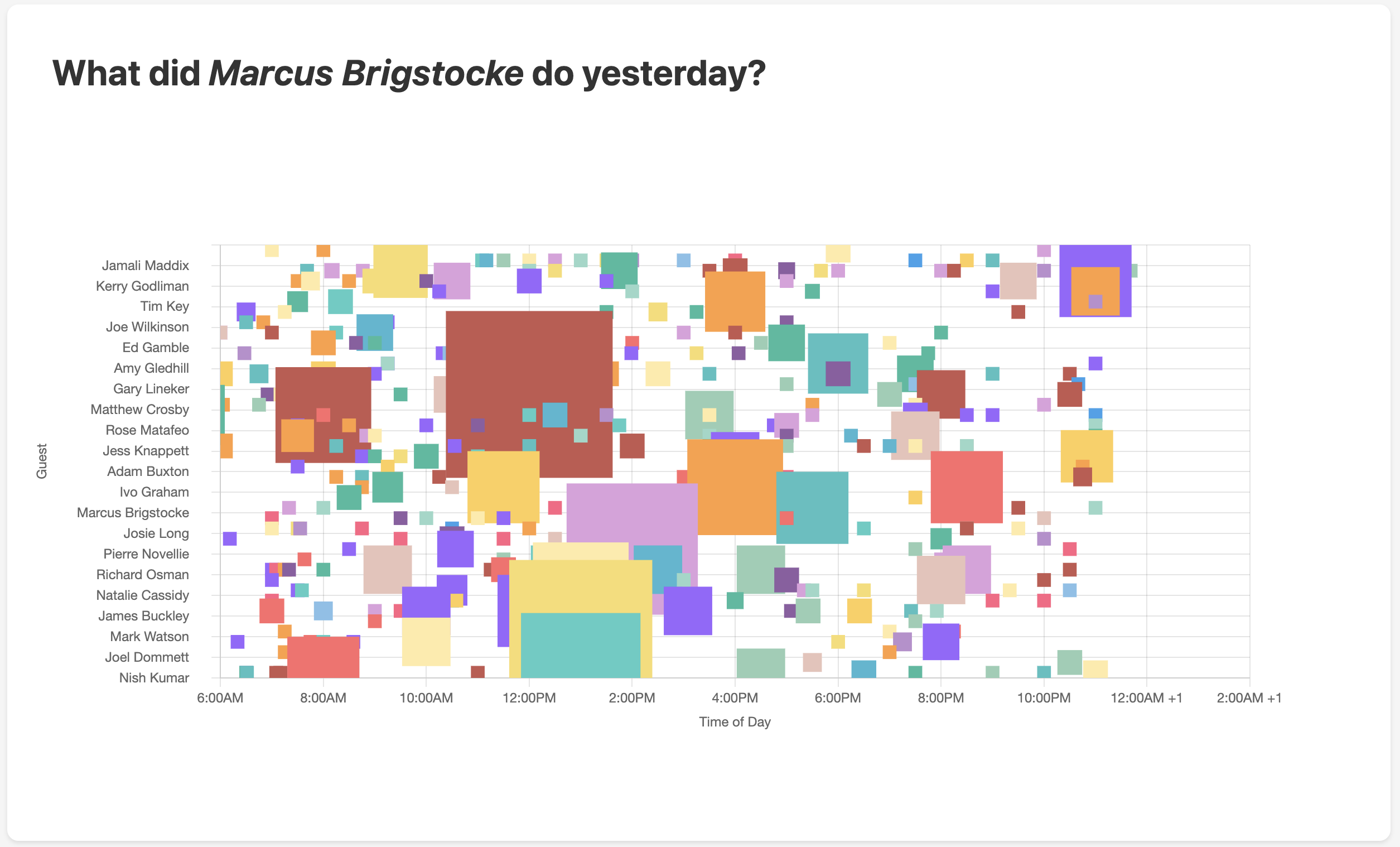

You did what?

Over the past year, this podcast has made me laugh so often, in the best of times as well as during the more stressful moments when lightness and humor are even more important.

I had this idea a month ago, started building one free weekend, and finished it after Max mentioned in last week's episode that he'd love to compare guests' days.

More serious motivations

Recently, I've tried to learn more about large language models. These AI models are a frontier of data science, and also increasingly important to public policy. Optimistic technologists, concerned researchers, lawyers, and policy makers are working on foundational questions - about alignment, fair use of internet-based IP, product liability, the economic impacts, and so much more.

The pace of change feels relentless, with new models and products every week. Most of the time I feel like I'm many miles behind, even though I use LLMs every day. Many of my incredibly smart friends, even those working in this space, feel the same way. It's really exciting, and humbling, and so much more.

As part of this push to learn, I've been exploring ideas for projects like this that use LLMs. I learn best when working directly with data and code. And with developer tools like Cursor, I'm less intimidated by ideas that involve software engineering.

My process

I had a reasonably clear sense of how I'd structure this project when the idea came to me. I would:

- Download audio files

- Transcribe them with Whisper

- Prompt an LLM to explore the transcriptions

- Visualize the output in a Gantt style chart

While I understood the structure, I was less clear on how each step would work. For example, how could I download the audio files? Claude helped me understand the many ways to accomplish each step. (For the first step, I used an RSS feed to download the files given that Apple and Spotify have "walled gardens" that prevent scripting.)

I started each step by prompting Cursor, and examined the proposed code. In most cases, the proposed code was a very strong start - maybe 80% done. We iterated, and as is the case with writing code without AI tools, this helped me understand what data issues I needed to solve, and ultimately, the output I wanted.

Once I started working on a step in Cursor, I rarely used Claude. It's much easier to provide critical context to Cursor, like my config.py file, and more seamless to debug and test code because Cursor can run terminal commands.

But after building out each step, I often returned to Claude to explore refinements and more general questions. I could have done this within Cursor, but I prefer the Claude UI, and find the responses are more balanced.

Prompting

This was the first time I had done "Product Prompt Engineering" (as opposed to conversational prompting in ChatGPT and Claude).

I used the research prompts from the appendix of Anthropic's Economic Index as a guide, and after writing initial drafts of my analysis prompt and system instructions, I asked Claude how I could improve both.

This was my system prompt:

You are analyzing a podcast transcript to extract key information about what the guest did yesterday.

Be precise and include information that is mentioned in the conversation between the podcast hosts, Max and David, and their guest. Refer to the guest, when appropriate, using their name.

If prompted to provide the time an action or event occurred, provide the time in the "HH:MM" format. If the time is unclear, provide a null value answer rather than guessing.

Ignore all product advertisements that may be accidentally included in the transcript. These advertisements are not the hosts or guest speaking; often start with "this episode is brought to you by ..."; and are several sentences long.

This was my analysis prompt:

Based on this podcast transcript, please answer the following questions about {guest_name}'s day yesterday:

**Wake-up Time:**

What time did {guest_name} wake up yesterday?

**Bed Time:**

What time did {guest_name} go to sleep in the evening yesterday?

**Daily Schedule:**

List {guest_name}'s activities from yesterday chronologically. For each event, provide:

- Start Time: When it started

- Part of Day: The general time period when the activity occurred (e.g., "morning", "afternoon", "evening", "night")

- Duration: The length in minutes

- Explicit Duration: True if the duration is explicitly referenced (e.g., "45 minutes", "an hour"), else False.

- Event: One sentence describing what happened

- Category: 1-3 word classification

- Participants: Who was involved, including {guest_name}

- Host Reaction: The host's reaction to that activity

Format each activity as:

Start Time: [time]

Part of Day: [1-2 words]

Duration: [minutes]

Explicit Duration: [boolean]

Event: [single sentence description]

Category: [1-3 words]

Participants: [names]

Host Reaction: [1-3 words]

**Output Format:**

Return valid JSON with this exact structure:

{{

"wake_time": "HH:MM" or null,

"bed_time": "HH:MM" or null,

"activities": [

{{

"time": "HH:MM" or null,

"part_of_day": "part",

"duration_minutes": number or null,

"explicit_duration": true|false,

"event": "description",

"category": "category",

"participants": ["name1", "name2"] or [],

"host_reaction": ["adjective1", "adjective2"] or null

}}

]

}}

**Transcript:**

{transcript}

I forgot to use a system prompt with OpenAI's Whisper transcription model.

Building with Cursor

Using Cursor shaved tens of hours off of this project. It was exceptionally helpful. And it exposed me to new ways of approaching data problems.

At the same time, Cursor occasionally failed to run simple commands for a very basic reason: It was using the wrong file path. That the LLM was so capable, and yet got some of the simplest details wrong, surprises me.

Cursor also led me into one particularly frustrating trap.

I had just finished building a series of functions to impute the occasional null activity time, and needed to solve two related issues caused by activities that crossed midnight. As a result, a few data points had imputed durations of nearly 24 hours.

I wrote a "single-shot" prompt (which means I provided a single example) to build a function to handle this edge case. In response, the LLM suggested it refactor all of the related functions. I told it to proceed, and Cursor produced a much shorter script. I was pleased.

But the refactored script threw an error at the very first step. After debugging that, I immediately noticed the set of rules was resolving very few of the nulls, unlike before. I asked Cursor to explain why the code was no longer effective, and it repeatedly suggested new code without effectively helping me see what had changed.

I was a little frustrated that I couldn't revert the refactoring, and lost confidence in my ability to prompt my way out of this. (I had been so close!)

So I decided to start again using the version of the script from the day before. I lost several hours of work, and had fallen into a trap that I'd heard about online: That if you're not diligent about version control and check-pointing, AI tools can make changes that shutdown your workflow.

Ultimately this detour was a learning experience. Having to rebuild the script made it much better: For example, in my second attempt, I was clearer about the order of my logic. And I was more hands-on with Cursor. In one case, it had created a nested function within another function, and then wrote a nearly identical function later on. I fixed that immediately.

Front-end development and "visual learning"

Before this, I had never built anything in HTML. Doing something new, plus getting close to the finish line, made this stage of my project fun and exciting.

The biggest limitation I faced with the front-end, however, was that the LLM cannot render - or "see" - the output. Initial versions of the website were art, and I laughed when the LLM responded in a congratulatory tone celebrating that I now had a working website. Here's a screenshot of an early version:

After some prompting, including explicitly asking for a Gantt chart, the output was much closer to what I wanted. Except half of the data was not shown. In its thinking blocks as we debugged, Claude analyzed the chart.js data, and reported that it had the same number of rows as the raw input data. After some Googling and more prompting, it suggested we change the "container size," solving the problem.

As a data scientist, I visually inspect almost everything. It's a low-cost way to check work, and helps me push complex workflows forward. Having better "sight" would make the LLM so much more useful.

Tireless LLM or system instructions?

On two unrelated occasions, the LLM didn't like it when I interrupted its debugging by prompting it with an example of the issue, or a solution. It seemed to ignore me, and kept working on the prior resolution path it had set out.

This could be because of something very simple included in the Cursor system prompt, for example: "Complete each step within a plan."

Or, is this connected to the nature of reinforcement learning? I'm curious if this is a common behavior with the current models, and why.

Closing thoughts

Model choice: I used Claude Sonnet 4 for all coding except for when I was trying to debug the refactored script. A Cursor issue meant I had to switch to OpenAI o3, which really struggled in comparison. The suggestions weren't as good, it was slower, and it missed context. I took a break when it struggled to open an example I provided, and then decided to rebuild from the prior day's version.

Project structure: Something very small, but helpful, was that I copied the project structure I use in my job. This made it easier for me to work on one step at a time, to understand how the prompt-generated code would fit together, and to debug issues later on.

Hot take: Sonnet 4 in Cursor with "lazy" prompting (e.g., "make shorter") is too agreeable. Most replies started with "Great idea." I know that's not true.

LLM uplift: in a simple sense, it was zero to one, and that made this exciting!

Visual learning: I'd be very surprised if OpenAI, Anthropic, etc. and software tool builders like Cursor and Framer aren't already working on this with reinforcement learning.

More abstraction: I clearly defined the imputation logic. Next time I would give the LLM more to do, if only to see where it goes.

What's next? There's a lot more I can learn in this sandbox. One idea? I deliberately asked Claude to answer subjective questions, and could ask the same prompt to other foundational models and compare.